Forward: As the content will make clear, I wrote the following post back at Easter. I hesitated to post it, couldn’t find the right pictures, and before I knew it Easter was long over and it no longer seemed appropriate. However I struggled to move on and write anything else, so I’ve decided to just put it out there. After all, the holiday is really only a framing device for the content, which is relevant any time.

The Lenten journey is over for one more year. Holy week has passed, and the sun has set on Easter Sunday, the day of Christ’s resurrection, the miracle the whole faith hangs on. In my adult life, especially in theater, I find people amazed that Easter is an important holiday, one they have to take into account when making schedules. “What do you mean, you can’t rehearse on Easter?” I get asked, “Isn’t it for children?”

My relationship with the church was always a little different. My mother isn’t Catholic, and so neither was my parents wedding, and there was no requirement to baptize my sister and I as children. Growing up, I sometimes went to mass with my dad. I loved the beautiful statues, especially Mary, but it bothered me that she was always standing on snakes. I looked at her serene porcelain face, at the gorgeous, arched stained glass windows, at the softly burning votive candles. The church always seemed to me to be a magical place, a little boring sometime, but filled with magic nevertheless.

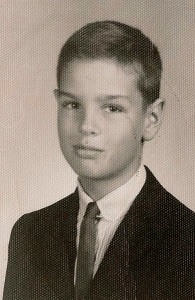

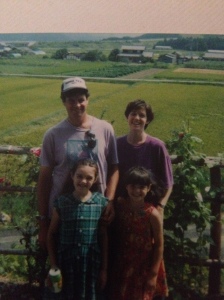

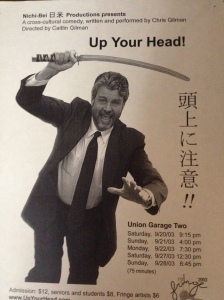

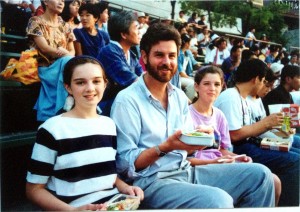

I became Catholic when I was sixteen. Baptism, first communion, confirmation and confession: Four rites in one lump ceremony. It was a day both laden with significance, and almost casual it its execution. Me and my sister officially joining the Catholic church, our friends the Luttios, one of two other Catholic families at our tiny missionary international school in Tokyo, were our Sponsors, our makeshift Godparents. Being at a tiny missionary international school had put pressure on my sister and I to form and proclaim a relationship with Jesus. Joining the Catholic church, the church my father and grandfather and generations of Gilmans back through history belonged to and prayed in, and the church that most teachers and students at the school didn’t understand or trust, was a way to do it on our terms.

Even before I joined the church I’d go to mass on Easter morning. I’d wear a new spring dress, which almost always required a coat over it. I’d sing Alleluia, sometimes in Japanese, and come home to a breakfast of pancakes and strawberries. I may not have understood the resurrection, but I loved the ritual.

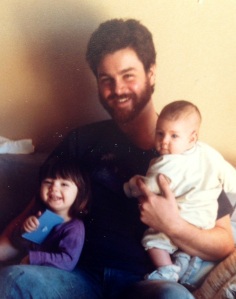

As an adult, and as a practicing Catholic, I still struggle to understand the resurrection, but I need it now more than ever. Sitting next to my stepmother in church on Easter morning, I listened as Father Whitney declared that our faith means Love is stronger than Death. That we think we know where the road is leading, and then it detours. Just over seven months since losing my father, and I am continuing to discover the ways in which his love remains, is reborn in me, in my sister and my stepmother, in those who remember him. The resurrection is grace over sin, life over fear, love over death.

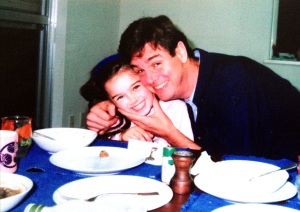

I went to St. Joseph’s for Easter service. I don’t go to mass every week, and I don’t make it to St. Joe’s every time I go to mass, It’s a half hour drive from where I live now, but it is my favorite. St. Joe’s is the church that drew my dad back in his early thirties after he spent his twenties wandering the country, driving cabs, working on fishing boats, and steadfastly ignoring his Catholic upbringing. St. Joe’s is the church we used to go to together, almost every Sunday night, when I was in college and he was divorced. He’d pick me up in the white truck, we’d go to mass, and then we’d go out to dinner, or go back to the Ballard house and make dinner and watch The West Wing. St. Joes is where he married my stepmother, proudly wearing his first tuxedo, and St. Joe’s is the church where we held his funeral mass, the altar decked in red roses and a giant framed picture of his professional smiling face.

I go there now when I can, and when I go, I always end up crying. It has become one of the few places in my life where I can let my guard down, where I can be that vulnerable, where I can both worship and mourn without having to explain myself.

I don’t talk a lot about being Catholic, especially in the theater. It’s usually the last thing people learn about me. I don’t talk about it because when people learn you’re Christian, they tend to make assumptions that I’d rather not go out of my way to disprove. I consider myself intelligent, I like whiskey and dirty jokes, and I don’t believe, and I have never believed that anyone holds a monopoly on truth, certainly not an institution as old and riddled with sin and scandal as the Roman Catholic Church. But my faith still means something to me, something more than the fact that it ties me to my father and to my ancestry, something more than my deep and abiding appreciation for rituals and putting on a great show.

It hinges on this day, on Easter Sunday, on the resurrection, on the fact that death may be the end of the road, but it is not necessarily the final say. On the idea that someway, somehow, those we have loved and lost remain, with us and with God.